Revisiting Iraq Part One: Saddam's WMD

The typical catch-all dismissal of the Iraq War's legitimacy is long overdue a correction

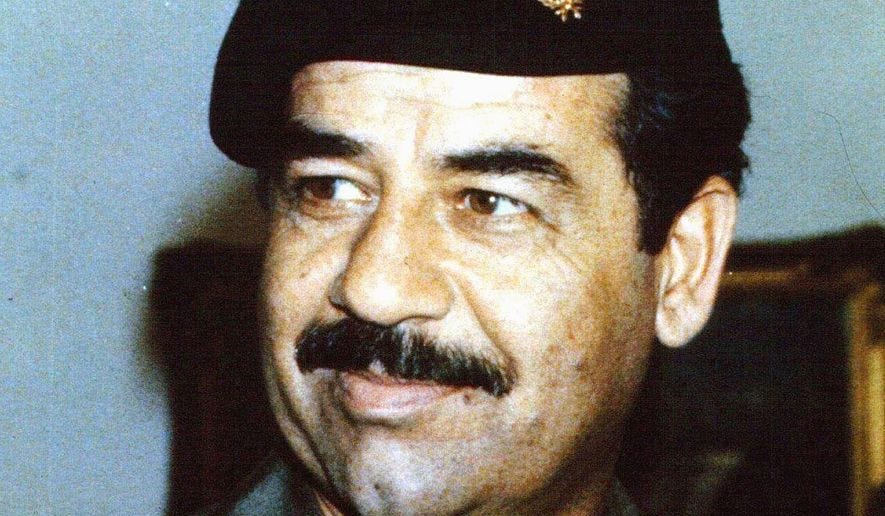

In the aftermath of the 1990-1991 Gulf War, which saw the US-led coalition liberate Kuwait after its invasion and annexation by Iraq, Saddam Husayn’s regime was placed under a heavy set of UN sanctions and resolutions which defined the terms for a cessation of conflict. By the early 2000s, Iraq had continually failed to adhere to the demands which underpinned this ceasefire, flirting with weapons proliferation and support for international terrorists. Amidst an intensifying post-9/11 landscape, the United States and Britain decided that enforcing these demands had a renewed priority for regional stability and for the security of the West. The result was the Iraq War, prosecuted by a multi-national coalition led by the US in 2003 under the codename Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)—OP TELIC in the UK. The invasion and its outcome remain intensely controversial, and no foreign policy decision since has really been able to escape from its shadow. No debate on any current or future defence policy can avoid this, and we are constantly revisiting the ostensible “lessons” of the war in Iraq as we once did with US involvement in Vietnam. Regardless of one’s belief in the justness, or otherwise, of the invasion or occupation of Iraq, any attempt to engage seriously with the topic requires that we push through the barrier of conventional myth: that OIF was prosecuted on the basis of a lie. Really, this notion is formed of two beliefs: that the Anglo-American rationale for invasion relied on exaggerated, or falsified, pre-war intelligence regarding Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD); and that this was compounded by a misbegotten fear of Iraq’s relationship with terrorism, notably al-Qaida, during the hysteria which followed the 9/11 terror attacks. This is the first of a two-part post looking at these two ideas respectively. In this post we turn our attention to the ever-persistent question of Saddam’s WMD.

The Shifting Burden of Proof

Any discussion about Iraq and weaponry should start by correcting course early on. The prevailing narrative—that war was declared based on a false assessment of pre-war intelligence regarding Iraq’s WMD capability—is itself incorrect, or at least incomplete. This is the case irrespective of one’s views about the extent to which Washington (and London) believed the intelligence they presented in the run up to the invasion. It wrongly shifts the burden of proof onto the US/UK, insinuating that the onus was on them to prove that Saddam’s Iraq possessed the weaponry that their intelligence agencies estimated in order to justify military intervention. But the reality is that while their pre-war estimates were much talked about in the lead-up to war, they were largely irrelevant to the casus belli. Following the 1991 Gulf War ceasefire, the Saddam Husayn regime’s possession of, and intention to posses, WMD was presumed and codified as a foundational base state of United Nations Security Council resolution (UNSCR) 687 which mandated a disarmament process—among other obligations—for Iraq and established the standards by which their compliance would be judged. UNSCR 687 brought with it the creation of the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), a body whose duty was to verify whether Iraq had disarmed as per the mandates laid out in the resolution by accounting for its weapons program in full and yielding all non-compliant weaponry to the commission’s inspectors. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was also brought in to inspect nuclear activities. The role of these UN weapons inspectors was not to verify that Iraq was armed by necessarily going looking for WMD, but to determine if Saddam had met his obligations to prove disarmament as per the mandates of the resolution. That distinction may be subtle, but it is important. Iraq’s guilt was already established as baseline fact in 1991, and thus there was no burden of proof on the weapons investigators or the US/UK in their enforcement. The "governing standard of Iraqi compliance” was not formed with any reference to pre-war intelligence estimates, but of prescribed measures to ensure Iraq was able to prove satisfaction of its obligations.

UNSCR 687 followed the 660-series of resolutions in the summer of 1990, and UNSCR 678 which:

Authorize[d] Member States […] to use all necessary means to uphold and implement resolution 660 (1990) and all subsequent relevant resolutions and to restore international peace and security in the area

In 1998, following Baghdad’s decision to cease co-operating with weapons inspectors from UNSCOM, the Security Council adopted resolution 1205 which condemned this as a “flagrant violation of resolution 687 (1991) and other relevant resolutions”. The report given by the committee’s chairman, Richard Butler, confirmed that Iraq was in material breach of its obligations. It was on account of this alone and not that of any additional intelligence estimates that Blair and the Clinton administration decided to enact Operation Desert Fox (ODF), a four day bombing campaign aimed at degrading Iraq’s WMD capability. For what its worth, post-2003, it seems that this campaign was more effective than anyone could have realised at the time. Nevertheless, Iraq’s material breach of UNSCR 687 provided a standalone legitimate basis, in accordance with UNSCR 678, on which to base military action.

UNSCOM was ultimately shut down in the fallout, and eventually replaced a year later by The United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) which operated under much the same mandate. In 2002, at which point the Iraq question had been inherited in the US by President George W. Bush, the UNSC once again adopted a resolution (UNSCR 1441) which:

Decide[d] that Iraq ha[d] been and remain[ed] in material breach of its obligations under relevant resolutions

Resolution 1441 provided a more permanent decision, stating that Iraq had (emphasis added):

…a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations under relevant resolutions of the Council; and accordingly [UNMOVIC] decide[d] to set up an enhanced inspection regime

In March 2003, UNMOVIC brought this period of “enhanced” inspections to a close, and with their report that month (often dubbed the “Cluster” document), they reaffirmed that Iraq was still in material breach of its disarmament obligations. They also restated that the ball was in Saddam’s court rather than that of the UNSCR enforcers (p.11):

The onus is clearly on Iraq to provide the requisite information or devise other ways in which UNMOVIC can gain confidence that Iraq’s declarations are correct and comprehensive.

It was on the basis of this breach that the Anglo-American Coalition opted to enforce the “final opportunity” which Iraq had decidedly failed to seize, and to take action pursuant to UNSCR 678 in using “all necessary means to uphold and implement […] relevant resolutions and to restore international peace and security in the area”. Within 2 weeks, the Gulf War ceasefire was ended and the invasion of Iraq began.

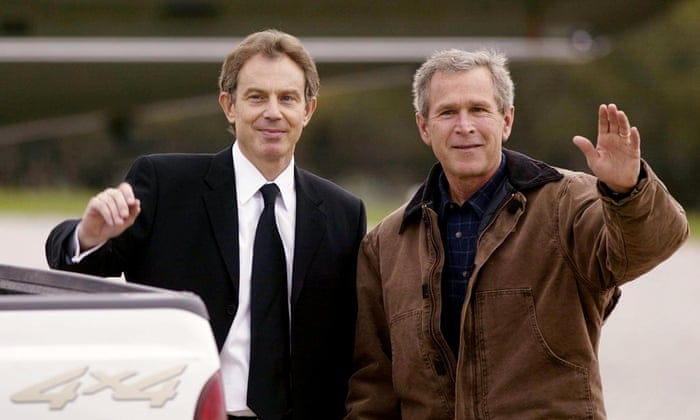

While the pre-war intelligence did not factor into the legal foundation for the war in Iraq, the extent to which its inaccuracies linger over our perception to this day is nevertheless understandable. For both the Americans and the British, much of this is due to political mismanagement by the governments at the time. For those of us in Britain, it is first worth noting that Tony Blair was always solid on Iraq and was not, as is commonly suggested in our commentary nowadays, simply swept along by the Americans’ fervour for war. In 1999, he delivered a speech to the Chicago Economic Club setting out The Doctrine of the International Community (sometimes referred to as ”The Blair Doctrine”) which was, to this day, possibly the best public evocation of the humanitarian interventionist position adopted by some on the Centre-Left following the end of the Cold War. The speech focussed primarily on the NATO intervention in the Balkans and the West’s role in preventing the coming genocide in Kosovo by the hand of Slobodan Milosevic. However, Blair was clear: our business with Milosevic may have been concluding, but we still had one more appointment waiting for us—an appointment for which we were overdue—in Baghdad. Anyone under the impression that Blair’s brand of liberal interventionism was unrealistic and utopian—the “if Iraq then what about Zimbabwe, or China, or North Korea?” crowd—would do well to remind themselves of that speech which expressly conceded that the West could not right every wrong, and instead laid down practical and sensible criteria for when the international community should attempt to do so. I mention the Chicago speech as it feels as though our collective national memory has fully bought into the accusation that Blair was Bush’s “poodle”, a common but particularly vapid and childish slight. Quite apart from the fact this doctrine was presented in April 1999 when the future president, at the time governor of Texas, was running on an isolationist policy platform urging the US to accept a more “humble” role in the world, it also serves to highlight the consistency in Blair’s thinking. After all, he committed airpower to the ODF bombing campaign back in 1998, he put pressure on Clinton to intervene in Kosovo and deal with Milosevic rather than the other way round, he committed British leadership to a military intervention in Sierra Leone in 2000, and he pledged to deploy troops to Afghanistan in 2001 even if the US would not. Far from being seduced into the Iraq decision, Blair was a longstanding believer in military intervention where necessary and in the need to finally deal with Saddam Husayn and conclude the conflict his regime started 13 years prior to OIF.

In 2002, as tensions grew between the international community and Iraq over the regime’s refusal to meet its disarmament obligations, it became clear that this inevitable appointment between the West and Saddam was drawing near. As a reminder, Saddam’s Iraq had a promiscuous history with WMD and was the only country in the region which had actually used them, both on its own soil and that of its neighbours. The regime deployed chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s; used them in a horrendous, genocidal campaign against Northern Iraq’s Kurdish population in the late 1980s; and employed their use against Shi’ites in a brutal repression of the 1991 Popular Uprising. More than 100,000 casualties, possibly in excess of double that number, likely occurred as a combined result. Worryingly, Iraq also went under the radar and ran a covert nuclear weapons program, starting in the 1970s, despite being a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as of 1969. The program was set back significantly when their Osiraq reactor was destroyed in an Israeli bombing operation in 1981, but it continued in full force until the Gulf War impositions. The UNSC resolutions that the regime continually flouted were, thus, understandably strict. And the importance of ensuring Saddam was not secretly rearming and that he could not continue his production and use of WMD was absolutely paramount, especially in light of his penchant for supporting global terrorist organisations as the West embarked on the War on Terror. Both the British and American administrations decided to solidify the public case for potential military action on the (correct) assumption that Saddam would, once again, fail to meet his obligations. In the process, however, they often helped to muddy the waters between a proper compliance-centred legal justification based on the 11-year history of UNSC resolutions, and an argument derived from their own pre-war intelligence estimates.

Plenty of mistakes were made here—not least because intelligence is, by its nature, always inexact and unsuitable to use as certain evidence of specific armament, especially in the case of Baghdad where Western agencies’ longstanding struggles to grapple with Iraqi WMD estimates were well-trodden—and opponents of the war have, as a result, had a much easier time shifting the narrative’s burden of proof away from Iraq and onto the Americans/British. In the UK, the best-known example of this was HM Government’s “September Dossier” and the Commons discussion around it, for which Parliament was recalled on the day of its release. This document put into the public domain a summary of pre-war WMD estimates held by British intelligence at the time based on numerous Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) reports. Predictably, many of these estimates turned out to be incorrect or at least imprecise, most notably reports—emphasised in Blair’s foreword to the dossier and his speech in the House of Commons—which suggested Iraq had the ability to deploy chemical and biological weapons within 45 minutes of a given order to do so. The reputational damage done by this document and the February dossier (often dubbed the “Dodgy Dossier”) which followed is difficult to overstate, and the terrible irony is that it likely did little to sway opinion at the time, mostly confirming assumptions which even opponents of a military intervention already held. The extent to which OIF was legitimate has since been, unfairly, judged by the public on the precision of these estimates and on the Coalition’s ability to prove them in the aftermath of the conflict. The case that the Iraq threat was rooted in noncompliance was very well established, and the attempt to add in these intelligence-based components to that definition was evidently an enormous error in judgement. This was even more the case for the Bush administration, who inherited from Bill Clinton a very clear, mature foundation codified in US law, and precedent set by ODF, with compliance at its core. For the Blair government, publishing intelligence in this way fit an ongoing theme of “government transparency” being stretched too far beyond its reasonable limits1. Both governments squandered an ironclad case, polluting it with unnecessary imprecision.

Post-Invasion Findings: Far From Nothing

As part of the US-led invasion, the Iraq Survey Group (ISG) was commissioned by Donald Rumsfeld to investigate WMD during the occupation of Iraq. This was a group of more than a thousand intelligence officials, scientists, WMD experts, and military personnel from the Coalition leads (the USA, Britain, and Australia). The ISG was initially headed up by former UNSCOM weapons inspector David Kay, who was then succeeded by fellow UNSCOM alumnus Charles Duelfer in January 2004. Its findings were published in September 2004 when the Duelfer Report was released (following an interim report delivered by Kay 11 months earlier), and an addendum was later added to this in March 2005. Given the expectations wrongly set by the pre-war intelligence, ISG findings have largely been panned and focus has, instead, been on specific estimates presented by government representatives in the lead-up to OIF which were not found. To reiterate: the trigger for enforcing the UNSC resolutions was a result of Saddam having already failed to comply with the “final opportunity” laid down in UNSCR 1441 as of March 2003, and so the findings of the ISG were irrelevant to the enforcement case for war which was already satisfied before the invasion began. Indeed, Saddam practically had free reign to destroy evidence before, and even during, the ISG investigation which rendered any intelligence-based arguments useless from the offset. Nevertheless, while the pre-war estimates turned out to be imprecise as we all now know, it is not correct to say that Iraq was innocent on the WMD charge. In fact, the majority of the ISG findings supported the case made by the Americans and British prior to the invasion and certainly corroborated the findings of UNMOVIC in 2003 which confirmed Iraq’s continued “material breach” of disarmament obligations and their failure to comply with the 687-mandated requirements and 1441’s “final opportunity”.

Post-1991, after the disarmament obligations came into effect, Saddam’s regime in Iraq instituted an elaborate and systematic operation of concealment. In compliance with Saddam’s paranoid security measures, no one agency or ministry of government was in charge of this mandate, and duties to conceal WMD activities instead overlapped between several departments. This included joint efforts between the Iraqi Intelligence Service (ISS; the Mukhabarat), the Special Security Organisation (SSO), the Military Industrial Commission (MIC), its parent the Ministry of Industry and Military Industrialisation (MIMI), and the Special Republican Guard (SRG). In May 1991, Saddam appointed his younger son, Qusay, as head of the new Concealment Operations Committee (COC). Iraq also established, in November 1993, a unit charged with “co-operating” with weapons inspectors: the National Monitoring Directorate (NMD). Though, in practice, this unit was tasked with tracking and reporting on the inspectors so that the aforementioned agencies could be warned of impending visits. In 1996, Saddam convened a sub-committee of the National Security Council (headed by Saddam himself, but often chaired by Qusay), the Special Security Committee, which had the express aim of overseeing concealment efforts. NMD reported to them directly to allow for swift and efficient action when necessary. The culture of fear-based silence which pervaded all of Iraqi society under Saddam certainly did not stop at weaponry. Scientists and personnel working on covert WMD activities would have known that they and their families faced unimaginable suffering were they to spill to UN weapons inspectors anything other than the lines fed by Saddam, Qusay, and the concealment program. Even after the regime was removed following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, ISG investigators could not easily determine the fate of these concealed operations by interviewing those involved. Many Iraqi scientists fled during OIF, and many were silenced or murdered by former regime elements to prevent them from giving information to the ISG. The WMD program was, as with the concealment operation, sliced and diced so finely as to ensure that no scientist, regardless of seniority, would necessarily be able to provide useful details about weapons operations, let alone a full picture. It’s also worth noting that, on top of the concealment machine, the regime ran a campaign of deception and distortion aimed at deterring Iraq’s arch-enemy—Khomeinist Iran—which attempted to promote the idea that Saddam did possess considerable quantities of WMD, notably nuclear weapons. Even senior regime officials on the eve of war in March 2003 believed that they possessed WMD ready to use (Duelfer vol I pp.65-66). It is evident, in hindsight, that some of the imprecisions in the West’s pre-war intelligence came from ideas seeded by the Iraqi regime itself which, to the end, believed that the US threats to enforce disarmament were bluffs.

Biological and Chemical Weapons

By 1995, UNSCOM and IAEA had been conducting inspections in Iraq for 4 years. But the defection of the Kamel brothers—specifically Husayn Kamel al-Majid, Saddam’s beloved son-in-law and cousin—proved that this concealment operation had outfoxed them at every turn. Husayn Kamel was previously head of the MIC and organised Iraq’s WMD programs. The information he provided upon his defection showed that the regime had managed to hide vast numbers of weapons from inspectors and, in particular, had offensive biological WMD (BWMD) programs which were continuing at high levels (pp.188-189). Saddam claimed, after the outcry that followed these revelations, that the Iraqi BWMD program and materials had since been destroyed, though notably the regime did not perform this dismantling under the supervision of UNSCOM (as mandated by the UNSC resolutions). However, as the ISG notes (Duelfer vol III, Biological warfare, pp.15-17), Saddam then began a new covert BWMD program from 1996 until the invasion of Iraq housed under the operational control of the Mukhabarat (IIS):

With the bulk of Iraq’s BW program in ruins, Iraq after 1996 continued small-scale BW-related efforts with the only remaining asset at Baghdad’s disposal— the know-how of the small band of BW scientists and technicians who carried out further work under the auspices of the Iraqi Intelligence Service.

Iraq also never ceased producing missiles, or ”delivery platforms”, for biological and chemical weapons (Duelfer vol III, Biological Warfare, p.46) and ran an active network for long-range missile procurement (Duelfer vol II, Delivery systems, p.2). We know that BWMD seed stocks were retained by the regime, which were discovered after the invasion (Duelfer vol III, Biological warfare, p.2). A number of scientists who would possess the knowledge required to reconstitute BWMD capability were retained also. Iraq, furthermore, maintained a significant number of undeclared dual-use facilities. In other words, compounds and equipment which may not have been producing BWMD during the inspection regime, but which would have been readily available for such a use when required. Some of these facilities would have been convertible to BWMD production in a matter of weeks (pp.226-228). These dual-use facilities were often manned or visited by individuals known to have been involved in the pre-Gulf War weapons program. The ISG confirmed that the Mukhabarat, who took a special place in Saddam’s concealment apparatus, worked continually to procure illicit dual-use material which remained undeclared to UNMOVIC by the NMD (Duelfer vol I, pp.53, 73). While the ISG report and media commentators might make a distinction between existing weaponry and production capability, practically there is little difference between a regime with existing stockpiles of WMD and one ready to manufacture such weapons (which would usually be produced largely on demand in the lead-up to conflict anyway).

This retention of capability—of scientific specialism, precursor materiel, dual-use facilities, delivery mechanisms, and intentional concealment—was likewise the case for chemical weapon production (Duelfer vol III, Chemical Warfare, pp.1-3). The ISG also found that the Mukhabarat maintained a set of covert laboratories used to research chemical agents and poisons using methods which included human experimentation. That the pre-war presentations given by Anglo-American administrations, notably Colin Powell’s infamous address to the UN Security Council in February 2003, appeared to focus on weapons stockpiles rather than capability was, again, a large error in judgement. As a consequence, much of the public still (incorrectly) believe that the rationale for OIF depended solely on non-existent physical stockpiles, and thus these ISG findings were largely ignored despite being clearly significant. In any case, is the status of WMD programs and production capability not surely more important than stockpiles (which would degrade over time)? We know from the ISG findings that Saddam always retained a desire to resume his WMD programs, which he intentionally kept in stasis, and was actively intending to do so as soon as UN-imposed sanctions were lifted. Given that Saddam had effectively neutered the impact of sanctions by 2001—another factor in the Anglo-American Coalition falling back to military coercion as the method of enforcement—one wonders how long these measures would have lasted. Saddam’s intention to reconstitute his programs is crucial to understanding the goal of his extensive concealment apparatus and the cover it gave to covert operations which kept WMD capability alive and left production as rapidly available as was practical while maintaining a façade of compliance. It’s also worth recognising that, by creating a distinction between active WMD production/ownership and "activities that could support full WMD reactivation" (Duelfer vol I, p.9) which did not exist under the "governing standard of Iraqi compliance", the ISG itself fundamentally deviated from UNSCR 687 and the obligations to which Iraq was subject.

Even if this distinction between stockpiles and production capability were useful, the question of potential BWMD and CWMD stockpiles remains unclosed to this day. No hard evidence was found for Iraq’s supposed destruction of BWMD agents, and the B/CWMD stockpiles catalogued by UNMOVIC in 1999 were never accounted for by the regime (p.224). Post-invasion, ISG was never able to find the few stockpiles which Iraq had actually admitted to having under pressure. We know that, during the invasion, the Iraqi security services organised an unparalleled campaign of looting and systematic destruction of CWMD sites, the purpose of which was a final attempt to sanitise and conceal evidence of WMD programs (Duelfer vol III, Chemical Warfare, pp.37, 78-79). This was confirmed by David Kay during his appearance at the Senate Armed Services Committee in January 2004 where he stated that, even once the ISG had concluded its investigation, this meant there would always be an “unresolvable ambiguity about what happened”.

For certain stockpiles, however, we do have some ideas. It seems very likely that some WMD material was smuggled out of the country and into Syria during the invasion. In the 1990s Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, Saddam’s deputy and closest advisor, was ordered to set up an intricate criminal smuggling network between Baghdad and Damascus in order to help evade the sanctions imposed on Iraq. The network made billions and the proceeds were often used to provide for a patronage network—distributed through the security services, tribes, and clerics—to help prop up the regime against any potential future revolt. It was this network which came under Islamic State control when former regime elements (FREs) fused with al-Qaidists during the post-Saddam insurgency. But more on that in the second post focussing on terror. While the network was primarily focussed on importing illicit material into Iraq, during OIF there was a large, noticeable uptick in considerable transfers going in the other direction. James Clapper, who later served as the Director of National Intelligence under Barack Obama, said that “the obvious conclusion one draws” is that the remnants of WMD were being smuggled into Syria. George Sada, an Iraqi general and military advisor to Saddam, has confirmed that he knows this to be the case. Other FREs who joined insurgency groups post-2003 were found to be in possession of likely remnants of Iraq’s weapons program. The al-Abud network, a faction of Jaysh Muhammad, was found to be in possession of CWMD and had begun to develop their own program using the expertise and resources which had been retained in Iraq by Saddam (Duelfer, Chemical Warfare, pp.94-95). Fortunately, their success was limited and discovered fairly swiftly. The movement which would ultimately become Islamic State (JTJ then al-Qaida in Iraq; AQI) had access to CWMD only a year after the invasion and it is likely that some of the CWMD we have seen used by the movement since 2003 was taken from the fallen regime’s stockpiles. As late as 2007 we know that former regime stock was being found. The CIA ran a clandestine operation in the early years of the occupation which has since become declassified, known as Operation Avarice, in which they repeatedly purchased old CWMD stock being sold by an anonymous Iraqi (likely a FRE) on the black market in order to destroy the weapons and prevent their falling into insurgents’ hands. This removed hundreds of Borak rockets, some containing fairly well-preserved sarin. Purchases dried up and the operation ended, but there is no evidence that this constituted the end of available stock—stock which the seller had, on at least one occasion, threatened to sell to insurgent groups. Reports from OIF show that Coalition troops had to face the reality of leftover CWMD stockpiles themselves, having been subjected to chemical attacks during the invasion. This was a threat taken incredibly seriously by Coalition forces at the time—incidentally, surely a waste of time and money if the CWMD which apparently never existed were knowingly invented by war propagandists? We also know that thousands of leftover chemical warheads were recovered post-invasion, and that several Americans and Iraqis were injured in the process. These included “roughly 5,000 chemical warheads, shells or aviation bombs” and we know of at least 600 troops who suffered chemical exposure during the occupation as a result of this leftover chemical stock. These leftover stockpiles of CWMD, which Iraq was mandated to destroy, were clearly a part of the war rationale, as voiced in speeches at the time. They are also clear and blatant violations of UNSCR 687. Therefore, even if we are to insinuate that Iraqi guilt is to be determined only if physical weaponry, rather than capability, was found (to reiterate: an insinuation not supported by the UNSCR resolutions, the compliance case for war, or even the intelligence-based case put forward at the time; but nevertheless the situation we seem to find ourselves in after the fact) then they are still guilty.

The Nuclear Question

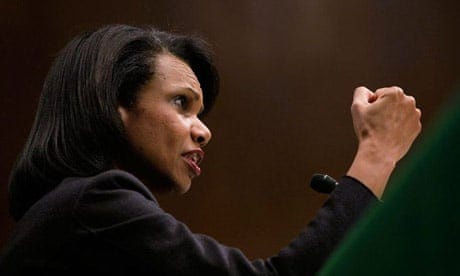

On top of the B/CWMD question, another unfortunate focus of the pre-war public presentation for OIF was the fear that Iraq would be in possession of an active nuclear weapons program. Again, the media focus and government presentations did much to tilt expectations incorrectly here. Condoleezza Rice’s claim that they did not “want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud” did not help matters. And again, after the invasion we did not find active nuclear weapons production to satisfy these errant expectations. But neither do our discoveries, as in the case of B/CWMD, support the idea that Saddam had given up on his nuclear program or indeed that Iraq was innocent on this front. We have learned that in February 1992 Qusay Husayn visited Dr. Mahdi Obeidi—the leader of Iraq’s nuclear centrifuge program—and ordered him to bury several components and a complete set of designs for a uranium-enriching centrifuge in his back garden (pp.150-154) so as to avoid their discovery by weapons inspectors. This was part of a wider concealment effort which went to incredible lengths including (p.149) deconstructing entire buildings and erecting compliant replicas in their place. The plans and parts remained buried until produced to the Americans by Dr. Obeidi after the war. The ISG found others who, under orders, had kept nuclear-related technology concealed from inspectors (Duelfer vol II p.73). We know that more broadly the Iraqi regime kept its nuclear weapons program frozen, purposefully leaving it in place instead of dismantling it as mandated. It continued to fund the Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission (IAEC) post-1991 to the very end (p.183). Equipment, facilities, and compartmentalised, specialist teams of “nuclear mujahideen” (Saddam’s term for the regime’s ~3,000 nuclear scientists) were all maintained as well (Duelfer vol II p.66). As with the biological and chemical weapons programs, Saddam was clearly maintaining this nuclear capability under the radar with the intention to reconstitute it as soon as the attention of the international community was drawn elsewhere (again, supported by ISG findings). The British pre-war intelligence reports which suggested that Iraq was attempting to buy Urainium from Niger in 1999 still seem sensible, though again publishing this uncertain intelligence in the September dossier was rash. Despite these reports being followed by falsified documents which rather distorted the whole issue, the fundamental case without them is not exactly un-compelling. The 2004 Butler review into Britain’s WMD intelligence failings concluded that the suggestion was credible and that the claims made by UK/US intelligence on this were “well-founded” (Butler p.123).

We also know, after acquiring documents post-invasion, that for two years preceding the war in Iraq, the Saddam regime had been engaged in talks with Pyongyang to purchase “a full production line to manufacture, under an Iraqi flag, the North Korean missile system”. This was a heinous breach of UN mandates. The nuclear-capable Rodong missiles boasted a range of ~2,000km, far exceeding the 150km limit put in place for Baghdad. Negotiations continued until at least February 2003, the month before OIF was instigated. Iraq had already put a down payment of $10 million, though the North Koreans—whose arms shipment to Yemen had been intercepted only 2 months before—ultimately got cold feet given the build-up of Coalition forces on Iraq’s border. It is worth noting that negotiations took place in Syria where the Assad regime acted as middleman for this illegal deal. Syria had long profiteered from the sanctions imposed on Iraq and from Izzat al-Douri’s smuggling network. The Iraqis ran the Rodong deal through a front company (“Al-Bashir Trading Company”) controlled by Qusay Husayn and their negotiations were fronted by a man named Munir Awad, who promptly fled to Syria during OIF where he was given government protection alongside a whole host of FREs, Douri included. For those who maintain that the Anglo-American Coalition was illegitimate in triggering OIF without a “second resolution” from the UN, let’s remind ourselves that Syria was a sitting member of the UN Security Council at the time. It’s also worth noting that no credit was really given to the Coalition after this discovery, who should have been able to boast of this as a disarmament success. However, OIF critics have always remained stuck in tallying up only the specific claims given during public presentations of pre-war intelligence (which knew nothing of this deal), so this was never the case. But looking more accurately at the broader case made for war, this was exactly the kind of illicit activity which, the rationale suggested, constituted an ongoing danger to the region.

Ceding the Disarmament Ground

Similarly, we rarely hear of the success that Iraq’s enforced disarmament brought globally. For example, we know that following OIF, Qaddafi’s Libya voluntarily capitulated their WMD programs, which included nuclear capability far outweighing Western intelligence estimates, and chemical materials. This point shouldn’t be oversold—talks had started between Qaddafi and Bush/Blair before the Iraq War. But the Anglo-Americans’ forceful demonstration of their non-proliferation commitment in 2003 clearly played a significant part and accelerated the process (pp.181-182). This, in turn, led to the dismantling of the AQ Khan network, a WMD black market run by (state-supported) Pakistani nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan and utilised by several rogue regimes including (though not limited to) all three members of the Axis of Evil: Iraq (pre-1990), North Korea, and Iran. Clear counter-proliferation “wins”, no? But the Bush and Blair governments were intolerably bad at defending their record when it came to Iraq. Partly, this was due to a shift in focus to democracy-building after the war which rather left the initial rationale—the removal of a longstanding regional threat—behind. That the war was largely successful in that regard was never really asserted. The administrations became tied up in so many fights surrounding their democracy-building failings that they left the threat-removal cause entirely undefended, allowing the current inaccurate, revisionist status quo to settle for good. The former Under Secretary of Defence for Policy, Doug Feith, wrote probably the best book available on the case for war based on his experience inside the Pentagon, and it documents this strange lack of defence from the US perspective (pp.470-478) alongside providing a just and scathing critique of the CIA’s performance. Several US senators attempted to mount a defence during the occupation, but the government had all-too-readily ceded that ground within the first year. That the war had successfully removed a latent (rather than blatant) threat was still a perfectly maintainable, and yet abandoned, position.

Of all the justifications for war, WMD has proved the most controversial and, as a direct result, the argument most associated with the invasion rationale. The cause of this piece is not to re-make the case for war but to argue that we are unable to (and unlikely to ever) have a serious conversation about Iraq while the overwhelming, prevailing narrative is that the WMD case was entirely unsubstantiated. It simply isn’t good enough to fall back on indolent, worn-out statements. ”We went to war on a lie”, “Iraq had no WMD”, and so on. By the time we went to war in March 2003, Saddam had repeatedly failed to meet the ceasefire terms for the preceding 12 years. We know that, further to having already breached his obligations and triggered compliance-enforcement, Saddam was in possession of weapons and WMD material which his regime was mandated to have destroyed as part of the resolutions put in place in 1991. We know that Iraq had a continued operation of concealment which was used to intentionally keep chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons programs and WMD capability alive under the noses of weapons inspectors. We know that he retained covert research labs and dual-use production facilities which would minimise the time needed to reconstitute “active” production. We know (p.227) that Saddam’s aim was to use his extensive state concealment apparatus to appear to comply with the UN-imposed disarmament obligations, but that he intended to rebuild WMD production the moment that sanctions were lifted. We know that he ran a network for illicit procurement and was in negotiations to purchase new, prohibited weaponry as late as February 2003. And we know that everything that we do know is only a bare minimum and by no means a complete account of Saddam’s WMD, the bulk of evidence having been destroyed, obfuscated, or relocated before and during the ISG investigation. The idea that “Saddam had no WMD” is wrong and insufficient as a blanket dismissal of the Iraq War’s legitimacy. Instead, the debate becomes: to what extent did the levels of WMD activity that we know the regime was undertaking constitute a latent threat? And that is a much more difficult case on which to come to a conclusion, especially when compounded by the undeniable threat posed by Saddam’s extensive terror nexus. See you in Part Two.

Arguably, the most disastrous legacy of the New Labour tenure, amidst a raft of unfortunate constitutional reforms, was deciding in 2003 to subject the decision to commit troops in Iraq to a vote in the House of Commons. Questions of military involvement, historically, had fallen entirely under a Prime Minister’s power as per the Royal Prerogative, and rightly so. But the Iraq votes in March 2003 were widely seen as establishing a precedent, paving the way for Cameron’s Syria vote in 2013 allowing a convention to emerge where governments seek Parliamentary approval for military deployment rather than submitting to Parliament after the fact.